Having recently returned from the art bun-fest that is the Venice Biennale, two main things strike me the quantity of surrealism on display and, as evidenced in the Russian and British pavilions, the importance of souvenirs.

I was pleasantly surprised by the selection on offer at the main exhibition hall in the Giardini from this year’s curator Massimiliano Gioni, which contained a large degree of outsider art to illustrate this year’s theme – The Encyclopedic Palace.

The inspiration behind this being the work of Italo-American self-taught artist Marino Auriti who, in the 1950s, conceived of an imaginary museum that was meant to house all worldly knowledge, bringing together the greatest discoveries of the human race, from the wheel to the satellite. Sadly Auriti did not live to see the invention of the Internet & the World Wide Web, which his ideas seem to presage. His large model for the museum was exhibited in the Arsenale and contains quotes offering good advice written around the outside of the building, in letraset (Watch that you don’t become greedy with your profits is my favourite, see pic above).

Given the theme, it was a unfortunate that Massimiliano Gioni chose not to confront the reality of contemporary life by including art that addresses information and communications technology nor be informed by the increasingly virtual lives we now live on-line, through social networking, etc. The only piece with reference to this (and it was an historic one) was a video montage of work by Stan Vanderbeek at the end. Included within this were pioneering early computer-generated film clips, although from the explanatory panels the audience wouldn’t have known this. Apart from this failing, there were many things to admire here and new names to discover, much of it historic. I have had to rein myself in and show only a small selection.

On view was a selection of 176 models, from Oliver Croy and Oliver Elser, The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz (1916- 1992) Insurance Clerk from Vienna. These intricately detailed models of a wide variety of vernacular architecture were discovered wrapped in garbage bags in a junk shop by the artist Oliver Croy, presumably left there on the death of their creator Peter Fritz. Little is known of Fritz, but he must have spent years working on these constructions using cardboard, matchboxes, wallpaper, foil and other everyday materials.

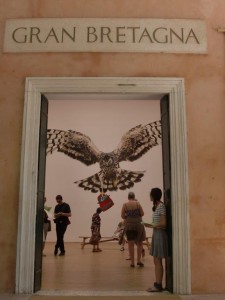

For the British pavilion, Jeremy Deller’s English Magic examined the notion of what Englishness might mean in the 21st-century by showing an eclectic variety of objects (and a film), some old (like ancient axe heads from the Museum of London), some made especially for this show and controversial, like the giant hawk and Range Rover mural (seen here), an ironic reference to an alleged incident of the shooting of a rare bird by Prince Harry (another work on this theme was pulled).

It was clear that Deller is really more of a curator than a maker, but it was none the worse for that. He also served tea and gave visitors a chance to print (or at least rubber-stamp) their own souvenir. Various bags, posters, books and a vinyl record of the music of the Melodians Steel Orchestra from South London (featured in his film) were available to buy as souvenirs. This show will be coming to Turner Contemporary in Margate next year.

The Russians also produced a souvenir, but only women were allowed to collect it. The artist Vadim Zakharov focused on the ancient Greek myth of Dana , the mother of Perseus by Zeus. Thousands of specially made golden coins rained down in their pavilion (the falling shower of gold referencing the seduction of Dana as an allegory for human desire and greed, but also to the corrupting influence of money). Women visitors, equipped with umbrellas to protect from the torrent of metal coins, were encouraged to collect them up and deposit them in a shoot, thus recycling them back into the artwork. As such, we guarantee the flow of material goods as an ongoing process as the blurb put it.

Gold might have been in abundance in Russia, but Spain showed their disgust with the current state of the economy by filling their pavilion almost entirely with a giant pile of rubble (and no doubt saving themselves money by not having to get special coins minted).

Among offsite projects, the highlight was famous Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s S.A.C.R.E.D, located in the beautiful setting of Sant Antonin church. Six large, heavy, Donald Judd-like bronze containers filled the space dramatically; inside each one a tableau depicting Mr Ai’s 81 day incarceration at the hands of his government in 2011. The installation was reportedly built in Korea to the artist’s direction, as Mr Ai is currently being kept by force in Beijing. Yes, it was very literal, but it did serve to remind us of the importance of Ai Weiwei keeping his profile high therefore a spot at the Biennale was an absolute must for this dissident artist to protect himself from a Chinese government who is not sure quite what to do with him, but knows that the world is watching. Visitors to the show, looking through the peepholes in the boxes, acted as witnesses to crimes against the individual. It was not too difficult to draw parallels with The Stations of the Cross, a Catholic ritual where a prayer is said in front of icons depicting each act against Christ as he is led to his death. Let us hope that this does not prove a portent for Ai Weiwei.